For cattle producers with cow-calf operations, you may also be interested in our October 2019 post on: Beef Bull Castration: Using Castration Banders, including the Callicrate SMART Bander. We also discuss our new approach of “delaying calf processing.” Be sure to check it out! Thanks!

Birth weight is a genetically heritable trait in beef cattle that has a direct impact on cow-calf management. On the surface, some might think that a bigger calf is better. However, big calves often cause difficult births, and if a farmer or rancher isn’t around to assist with the birth, they can end up with a dead calf or, in some cases, a dead cow. A small, live calf is much easier to sell in the fall than a dead one! Plus, with quality genetics, many of the smaller-born calves will weigh just as much as their heavier-born companions in the fall. On our farm we aim for a 65-75 lb birth weight. Last year we had one calf born at 110 lbs. Luckily we were present during the birth – we had to pull the calf, and would prefer to avoid having to deal with a calf born that big in the future.

Birth weight is a genetically heritable trait in beef cattle that has a direct impact on cow-calf management. On the surface, some might think that a bigger calf is better. However, big calves often cause difficult births, and if a farmer or rancher isn’t around to assist with the birth, they can end up with a dead calf or, in some cases, a dead cow. A small, live calf is much easier to sell in the fall than a dead one! Plus, with quality genetics, many of the smaller-born calves will weigh just as much as their heavier-born companions in the fall. On our farm we aim for a 65-75 lb birth weight. Last year we had one calf born at 110 lbs. Luckily we were present during the birth – we had to pull the calf, and would prefer to avoid having to deal with a calf born that big in the future.

Since birth weight is so important, good managers often attempt to collect weights on most of their calves around the time of birth. Seed stock producers do this routinely, as birth weight, along with assisted birthings are data they report to calculate EPD’s (expected progeny differences used to evaluate bulls). Commercial producers often times will guess a calf’s birth weight, or place them in categories (i.e. small, medium, large).

The most accurate method used to collect calf birth weights is by weighing each calf with a scale. We use a spring scale that can be carried out in the field. The calf is placed in a weigh sling and picked up with the scale. Simple as that. This method requires some extra work, and can be difficult to do when the momma cow is breathing down your neck trying to protect her calf.

The most accurate method used to collect calf birth weights is by weighing each calf with a scale. We use a spring scale that can be carried out in the field. The calf is placed in a weigh sling and picked up with the scale. Simple as that. This method requires some extra work, and can be difficult to do when the momma cow is breathing down your neck trying to protect her calf.

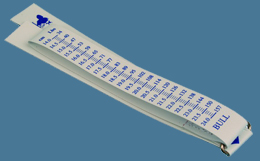

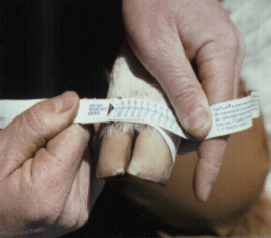

A less accurate, but quick method to estimate calf birth weight is the calf scale tape. A while back, Marshall Ruble, from Iowa State University, found a strong correlation between a calf’s hoof circumference and its birth weight. He determined that you could get a pretty good estimate of calf weight by simply measuring the circumference of the hoof. Ruble developed a simple tape that can be placed around a newborn calf’s hoof and gives an easy-to-read weight. One side of the tape is used for bulls, the other for heifers.

We used the calf scale tape last year and followed up by taking hoof diameter and spring scale weight on a couple of calves. Though our sample size was low, we found that the tape gave weights very close to our scale weights. A South Dakota State University study negated some of the claims of the Ruble Calf Scale, finding a relatively poor correlation between hoof circumference and birth weight, so you can take the information with a grain of salt. Some folks swear by the calf tape, and others refuse to use it.

A number of methods are available for estimating calf birth weights, including visual guesses, hoof circumference and actual scale measurements, and each has its strengths and weaknesses. If you’re interested in collecting birth weights of your calves to help improve management and make selection decisions, give these methods a try.

For cattle producers with cow-calf operations, you may also be interested in our October 2019 post on: Beef Bull Castration: Using Castration Banders, including the Callicrate SMART Bander